I’m giving a talk this Wednesday at a local Meetup group on the Tor project, and I wanted to log some of the notes I took as I read the design paper.

Most of it is taken word-for-word, and so I do not claim this to be a work of my own origin. It is intended to be a highly-condensed well of Tor knowledge to which I can frequently refer.

In addition, some of the information may be outdated, since this paper was written in 2004. Buyer beware :)

These notes only cover the technical details outlined in the first part of section 4, as this is what I was most interested in (after having read the entire paper, of course).

Really, though, you should read the paper yourself. Don’t depend only on what I think is important enough to include in these notes!

OP = Onion proxy

OR = Onion router

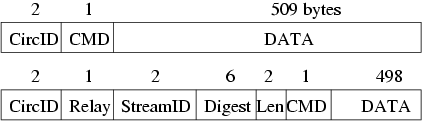

4.1 Cells

Onion routers communicate with one another, and with users' OPs, via TLS connections with ephemeral keys. Traffic passes along these connections in fixed-size cells.

- Fixed size, 512 bytes

- Consists of header and payload

- The header contains:

- A circuit identifier (

circID) that identifies which circuit the cell refers to. - Many circuits can be multiplexed over the single TLS connection.

- Includes a command to describe what to do with the cell’s payload.

circID’s are connection specific: each circuit has a different circID on each OP/OR or OR/OR connection it traverses.

- A circuit identifier (

- Based on their command, cells are either:

controlcells - Always interpreted by the node that receives them.- Commands are:

padding(currently used for keepalive, but also usable for link padding)createorcreated(used to setup a new circuit)destroy(to tear down a circuit)

- Commands are:

- or

relaycells - Carry end-to-end stream data.- Have an additional header (the relay header) at the front of the payload.

- The additional header contains:

streamID- Many streams can be multiplexed over a circuit.- End-to-end checksum.

- Length of relay payload.

- Relay commands can be one of:

relay data(for data flowing down the stream)relay begin(to open a stream)relay end(to close a stream cleanly)relay teardown(to close a broken stream)relay connected(to notify the OP that a relay begin has succeeded)relay extendand relay extended (to extend the circuit by a hop, and to acknowledge)relay truncateand relay truncated (to tear down only part of the circuit, and to acknowledge)relay sendme(used for congestion control)relay drop(used to implement long-range dummies).

- Have an additional header (the relay header) at the front of the payload.

4.2 Circuits and Streams

- Again, TCP streams are multiplexed over a single circuit (original OR design had one circuit per TCP stream).

- To avoid delays, circuits are create preemptively.

- OPs consider rotating to a new circuit once a minute

- only a limited number of requests can be linked to each other through any given exit node

- since circuits are built in the background, circuits are fault-tolerant

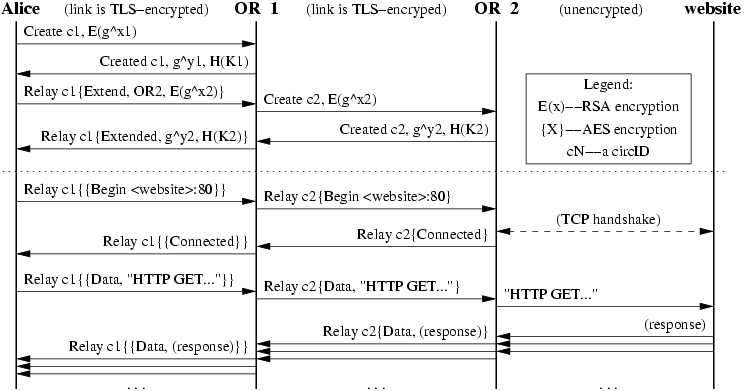

Figure 1: Alice builds a two-hop circuit and begins fetching a web page.

Figure 1: Alice builds a two-hop circuit and begins fetching a web page.

Constructing a Circuit

A user’s OP constructs circuits incrementally, negotiating a symmetric key with each OR on the circuit, one hop at a time.

-

Alice, the OP, sends Bob, the first OR in her chosen path, a

createcell.- She chooses a new

circIDCAB that hasn’t been created before on the connection from her to Bob. - The

createcell’s payload contains the first half of the Diffie-Hellman handshake (gx1), encrypted to the onion key of the OR.

- She chooses a new

-

Bob responds with a

createdcell containing gy1 along with a hash of the negotiated keyK = gxy.- Alice and bob can now send each other relay cells encrypted with the negotiated symmetric key (actually, the negotiated key is used to derive two symmetric keys: one for each direction).

-

To extend the circuit further, Alice sends a

relay extendcell to Bob, specifying the address of the next OR (call her Carol), and an encrypted gx2 for her. -

Bob copies the half-handshake into a

createcell and passes it to Carol to extend the circuit.- Bob chooses a new

circIDCBC not currently used on the connection between him and Carol. - Alice never needs to know this

circID; only Bob associates CAB on his connection with Alice to CBC on his connection with Carol.

- Bob chooses a new

-

Carol responds with a

createdcell, and Bob wraps the payload into arelay extendedcell and passes it back to Alice.- Now the circuit is extended to Carol.

- Alice and Carol share a common key K2 = gx2yx.

-

To extend the circuit to a third node or beyond, repeat steps 3 - 5.

- Essentially, this is always telling the last node in the circuit to extend one hop further.

This circuit-level handshake protocol achieves several important properties:

-

It achieves unilateral entity authentication:

- Alice knows she’s handshaking with the OR, but the OR doesn’t care who is opening the circuit— Alice uses no public key and remains anonymous.

-

It achieves unilateral key authentication:

- Alice and the OR agree on a key, and Alice knows only the OR learns it.

-

It achieves forward secrecy.

- No keys used in the connection are ever cached or otherwise saved, so any captured cells will never be able to be decrypted at a future date.

Circuit-level handshake protocol:

Alice -> Bob : EPKBob(gx)

Bob -> Alice : gy, H(K|“handshake”)

Legend:

EPKBob(.) = Encryption with Bob’s public key.

H = A secure hash function.

| = Concatenation.

Relay Cells

Now that Alice has established a circuit, she now has shared keys with each OR in the circuit and can relays cells:

- Upon receiving a relay cell, an OR looks up the corresponding circuit, and decrypts the relay header and payload with the session key for that circuit.

- If the cell is heading away from Alice, the OR, having decrypted the cell using its shared key with Alice, checks if the decrypted cell has a valid digest.

- As an optimization, the first two bytes of the integrity check are zero, so in most cases we can avoid computing the hash.

- If valid:

- It accepts the relay cell and processes it.

- If not valid:

- The OR looks up the

circIDand OR for the next step in the circuit, replaces thecircIDas appropriate, and sends the decrypted relay cell to the next OR.

- The OR looks up the

- If the OR at the end of the circuit receives an unrecognized relay cell, an error has occurred, and the circuit is torn down.

Incoming cells (to Alice, the OP):

- They iteratively unwrap the relay header and payload with the session keys shared with each OR on the circuit, from the closest to farthest.

- If at any stage the digest is valid, the cell must have originated at the OR whose encryption has just been removed.

To construct a relay cell addressed to a given OR, Alice assigns the digest, and then iteratively encrypts the cell payload (that is, the relay header and payload) with the symmetric key of each hop up to that OR.

Because the digest is encrypted to a different value at each step, only at the targeted OR will it have a meaningful value.

This leaky pipe circuit topology allows Alice’s streams to exit at different ORs on a single circuit. Alice may choose different exit points because of their exit policies, or to keep the ORs from knowing that two streams originate from the same person.

When an OR later replies to Alice with a relay cell, it encrypts the cell’s relay header and payload with the single key it shares with Alice, and sends the cell back toward Alice along the circuit. Subsequent ORs add further layers of encryption as they relay the cell back to Alice.

To tear down a circuit, Alice sends a destroy control cell to each OR in the circuit:

- Each OR in the circuit receives the destroy cell, closes all streams on that circuit, and passes a new destroy cell forward.

Just as circuits can be built incrementally, they can be torn down incrementally:

- Alice can send a relay truncate cell to a single OR on a circuit.

- That OR then sends a destroy cell forward, and acknowledges with a relay truncated cell.

- Alice can then extend the circuit to different nodes, without signaling to the intermediate nodes (or a limited observer) that she has changed her circuit.

Similarly, if a node on the circuit goes down, the adjacent node can send a relay truncated cell back to Alice.

- Thus the “break a node and see which circuits go down” attack is weakened.

4.3 Opening and Closing Streams

Opening a Stream

-

When Alice’s application wants a TCP connection to a given address and port, it asks the OP (via SOCKS) to make the connection.

-

The OP chooses a node from the newest open circuit (or creates one if none are open) to be the exit node. The chosen node is usually the last node, but it doesn’t have to be (depends on node exit policies).

-

The OP then opens the stream by sending this exit node a

relay begincell, using a newstreamID. Once the exit node connects to the responder (the remote host), it replies with arelay connectedcell. Upon receipt of this, the OP notifies the application that everything is set. -

The OP now accepts data from the application’s TCP stream, packaging it into

relay datacells and sending those cells along the circuit to the chosen OR .

-

-

Care must be taken that the application doesn’t ask the host DNS resolver to lookup the hostname!

- If the application does DNS resolution first, Alice thereby reveals her destination to the remote DNS server, rather than sending the hostname through the Tor network to be resolved at the far end. Common applications like Mozilla and SSH have this flaw.

Closing a Stream

-

Closing a Tor stream is analogous to closing a TCP stream: it uses a two-step handshake for normal operation, or a onestep handshake for errors.

- If the stream closes abnormally, the adjacent node simply sends a

relay teardowncell. - If the stream closes normally, the node sends a relay end cell down the circuit, and the other side responds with its own

relay endcell.

- If the stream closes abnormally, the adjacent node simply sends a

-

Because all relay cells use layered encryption, only the destination OR knows that a given relay cell is a request to close a stream.

- This two-step handshake allows Tor to support TCP-based applications that use half-closed connections.